The Bank of Canada is set to make its final decision of 2022 on December 7th - and nearly everyone paying attention thinks Tiff Macklem will increase rates by either 25 or 50 basis points. On the side of 25 are those who think Canada’s economy was being artificially supported by low interest rates and an extended housing boom, and might already be contracting. On the side of 50 are those who think it’s dangerous that those darn workers keep asking for raises (even when those ‘raises’ still mean real wage cuts).

There are many reasons why the wage-price spiral boogey-person is being raised (but mostly, class war), and good reasons why it isn’t anywhere close to the factor that bankers and employers are pretending it is.

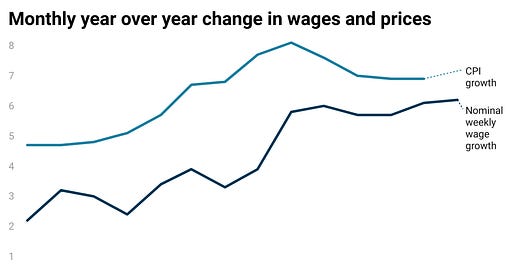

Nominal wages (not adjusted for inflation) are increasing, but they still haven’t caught up with inflation (there are multiple measures of wages, and I chose the one that showed the healthiest growth - weekly wages including overtime). As inflation falls in 2023, though, we can expect there to be a period where nominal wages continue to rise. Look for the usual suspects to shout about the sky falling, and workers are expecting inflation to be here to stay. Not so. In fact, this would be a healthy sign that workers are able to make up real wage losses, not any kind of sign about unanchored expectations.

Historical evidence shows wage-price spirals are rare, and we are not at risk of one now.

A paper published by the European Central Bank (ECB) in 2021, found that the link between wages and prices is no longer as strong as it used to be in the United States (they looked at data from 1960-2018). Part of this may be because of ‘expectations’, regular people’s belief that the central bank will do what it takes to keep inflation close to 2%. But they also found more compelling reasons - globalization and concentration of market power.

These two factors … may even be interrelated as rising markups have been concentrated among large international companies (see for instance Autor et al. (2017)) who benefit from global networks of factors of production and are able to offset the impact of wage shocks. p.3, ECB Working Paper Series No 2583

Wages are part of a whole array of other input costs - energy, raw materials, machinery. If domestic wages are a smaller fraction of overall input costs now than they were in the 70’s and 80’s, it makes sense that domestic wage increases are going to have a smaller impact on prices now as well. And increasing market power means that the big players in the global economy have the ability to keep wages low, set prices where they want to, and shift production if they have to. All of this is bad for workers and consumers, but it means that wage-price spirals are less likely.

The International Monetary Fund also has a paper out, looking at the historical evidence for wage-price spirals. They’re particularly interested in macro-economic scenarios that are similar to the one we’re in right now, where we have increasing inflation, higher nominal wages but falling real wages, and falling unemployment.

Researchers found 22 episodes that fit the bill, and then looked at what happened in the quarters following. You can see that real wage growth lags CPI, and then continues to increase even as CPI falls again. The paper’s explanation is that tighter labour markets enable workers to make up real wage losses over the year or two following the ‘episode’, and that this has not historically resulted in extending inflationary periods.

Back to the class war

If wage-price spirals aren’t real, why do Tiff Macklem and the Bank of Canada (and others) spend so much time talking about them? It’s always been true that wage-price spirals are useful narratives for those who would like to undermine workers’ power. But the answer is also that they probably can’t do much about the global causes of inflation, but they can shrink the Canadian economy and declare a win. The “easiest” way to shrink the economy is to suppress wages and increase unemployment. We should make it much harder. There’s no reason that workers should bear the brunt of the cost here, not when corporate profits are at historic highs and government revenue is solid.

This is especially true in Canada, because as John Rapley pointed out in the Globe and Mail this week, the Bank of Canada has been engaging in a different kind of class war for the past decade - keeping rates low and fostering a real estate boom that has priced a significant fraction of the population out of ever being able to buy a home.