Labour shortages are usually good for workers

The latest data on job vacancies is out, and there is a lot to unpack.

Some history

One of my first ever blog articles was on job vacancies, a big issue in Canada following the recovery from the financial crisis. We had a two-speed economy in 2012 - oil and gas producing provinces were booming and the rest of Canada was still sluggishly picking up the pieces from the recession. And by 2013 the Minister of Employment, Jason Kenney, really wanted to know why unemployed workers from across Canada weren’t moving to Alberta to serve coffee (I heard many, many times about the need to act on labour shortages because of long lines at Tim Hortons in northern Alberta. Don’t mess with people’s access to coffee, I guess.)

This handwringing about labour shortages and what to do about it led Statistics Canada to revamp the information they collected on job vacancies. In 2011 the Survey of Employment, Payrolls and Hours (SEPH) added two questions - a) do you have vacancies, and b) how many? This really wasn’t enough to paint a good picture - so in 2015 Statistics Canada launched the Job Vacancy and Wage Survey (JVWS), that added some pretty important details - wage offered, duration of vacancy, level of education sought, level of experience sought, whether the job is full-time or part-time, permanent, temporary, or seasonal.

All of this helps paint a picture of *why* the job is vacant - are there not enough workers with the skill-set or experience employers are looking for - or are the wages & hours being offered insufficient.

One of the reasons that the Conservative government wanted this data was to justify increasing the scale of workers available through the Temporary Foreign Worker Program. By the time the JVWS got up and running the price of oil had crashed and the Conservative government was defeated, changing the conversation somewhat.

But now a return to low unemployment levels alongside elevated inflation has restarted the conversation, and as governments think about what they should do (if anything) to help employers fill vacant jobs, we have data!

Employers are reporting lots of jobs available

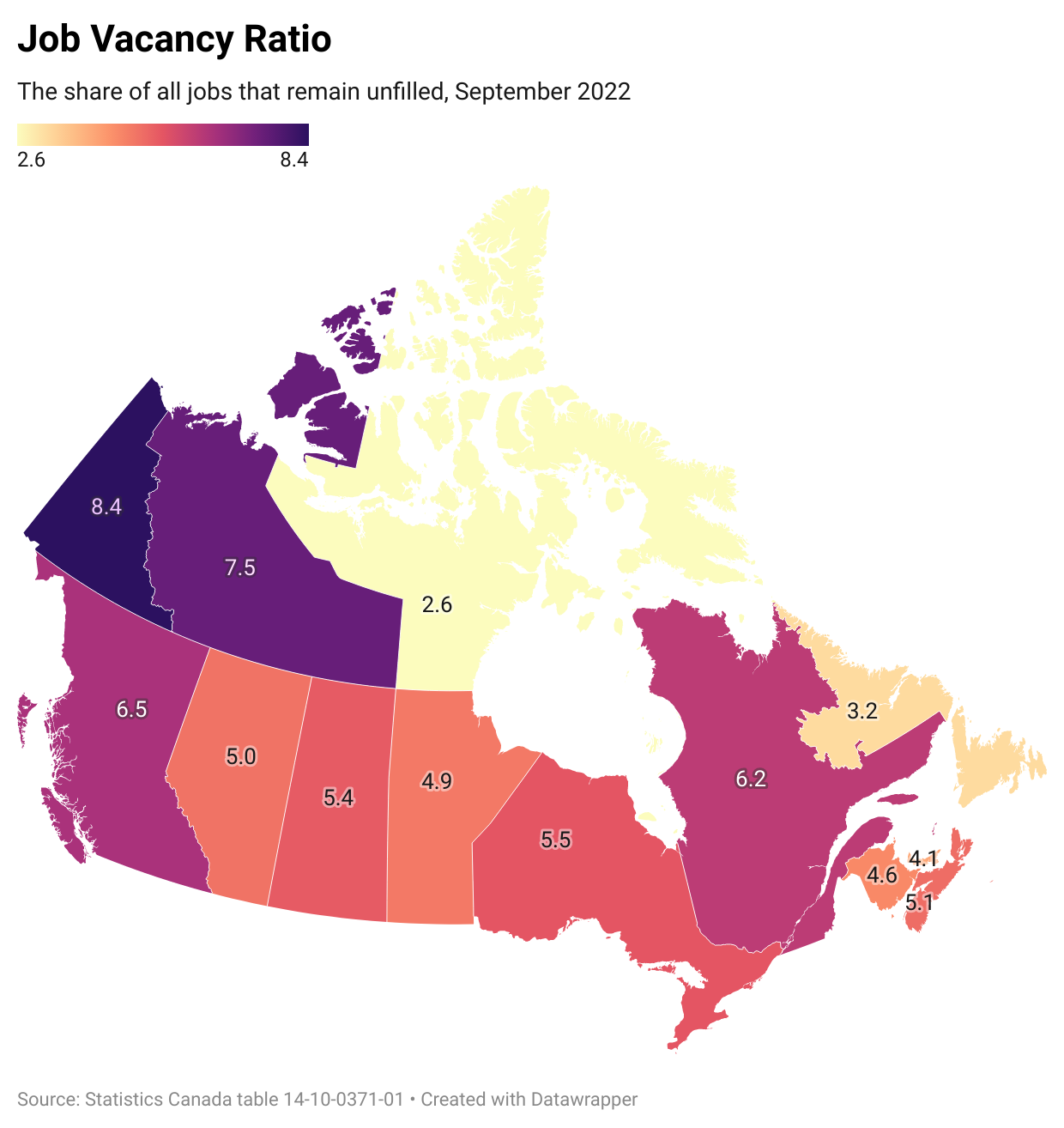

There are two main statistics that come out of the JVWS - the first is the ratio of vacant jobs to total labour demand (jobs that are filled + jobs that are vacant). For 2018 and 2019, job vacancies represented about 3% of total labour demand, since Q3 2021 it’s been over 5%. The most recent data, September 2022, is shown on the map above for all of the provinces and territories. The Canada-wide number fell slightly compared to September 2021 (see table 14-10-0371-01 for monthly data), but as usual there are regional differences. Quebec and BC have the highest proportion of job vacancies among the provinces, but this is trending down compared to last September when both provinces hit their peaks (trend not shown on the map).

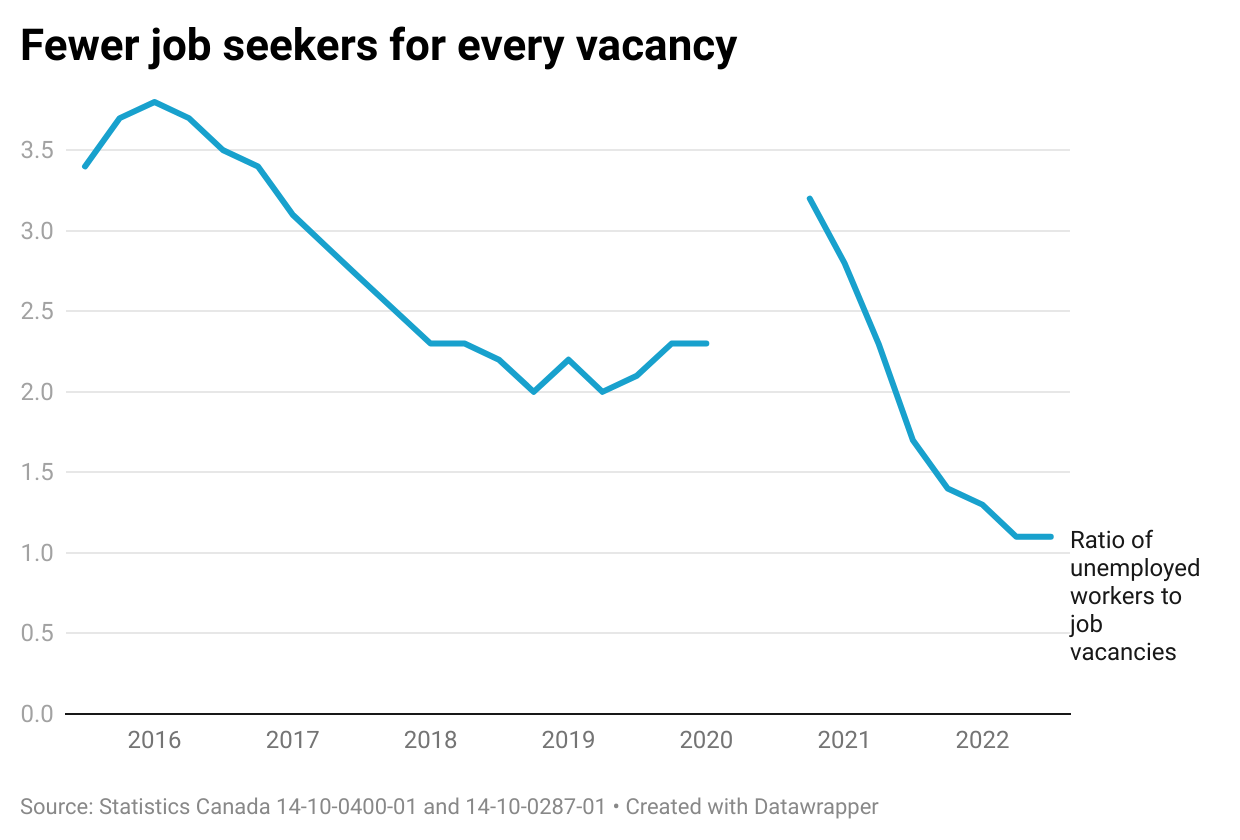

The second broad measure is the number of unemployed workers for each job vacancy. From April to September 2022, there was an average of 1.1 unemployed workers for every job vacancy. Yikes.

What kind of jobs, what kind of wages

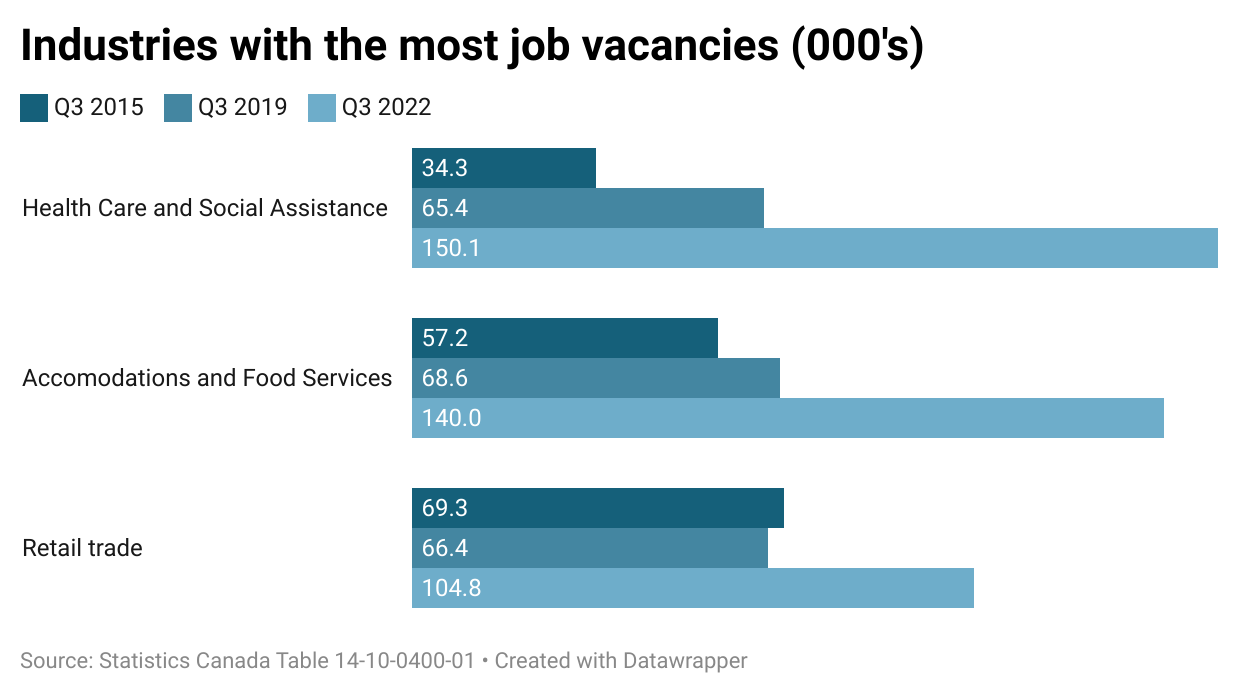

Between the third quarter of 2019 and the third quarter of 2022, the number of job vacancies almost doubled - from 540,000 open jobs to 960,000. Interestingly though, the three industries with the most job vacancies have remained the same since 2015, and these three industries account for almost half of that increase and 40% of all current job vacancies. The big shift has been Health Care and Social Assistance moving from #3 up to #1. Provincial underfunding of health care, and wage austerity in the broader public sector have contributed to this surge of vacancies as the pandemic continues on.

It makes sense that both Accommodations and Food Services, and Retail Trade usually have higher rates of job vacancies. These jobs tend to offer lower wages, more precarious hours, and have high rates of turnover. Some employers are continuously advertising with the expectation that some fraction of their current employees are going to leave for a better job soon. These industries have also been disrupted by the knock-on effects of a global pandemic & widespread inflation, and may not have settled out into a ‘new normal’.

Real wages stagnate despite record job vacancies

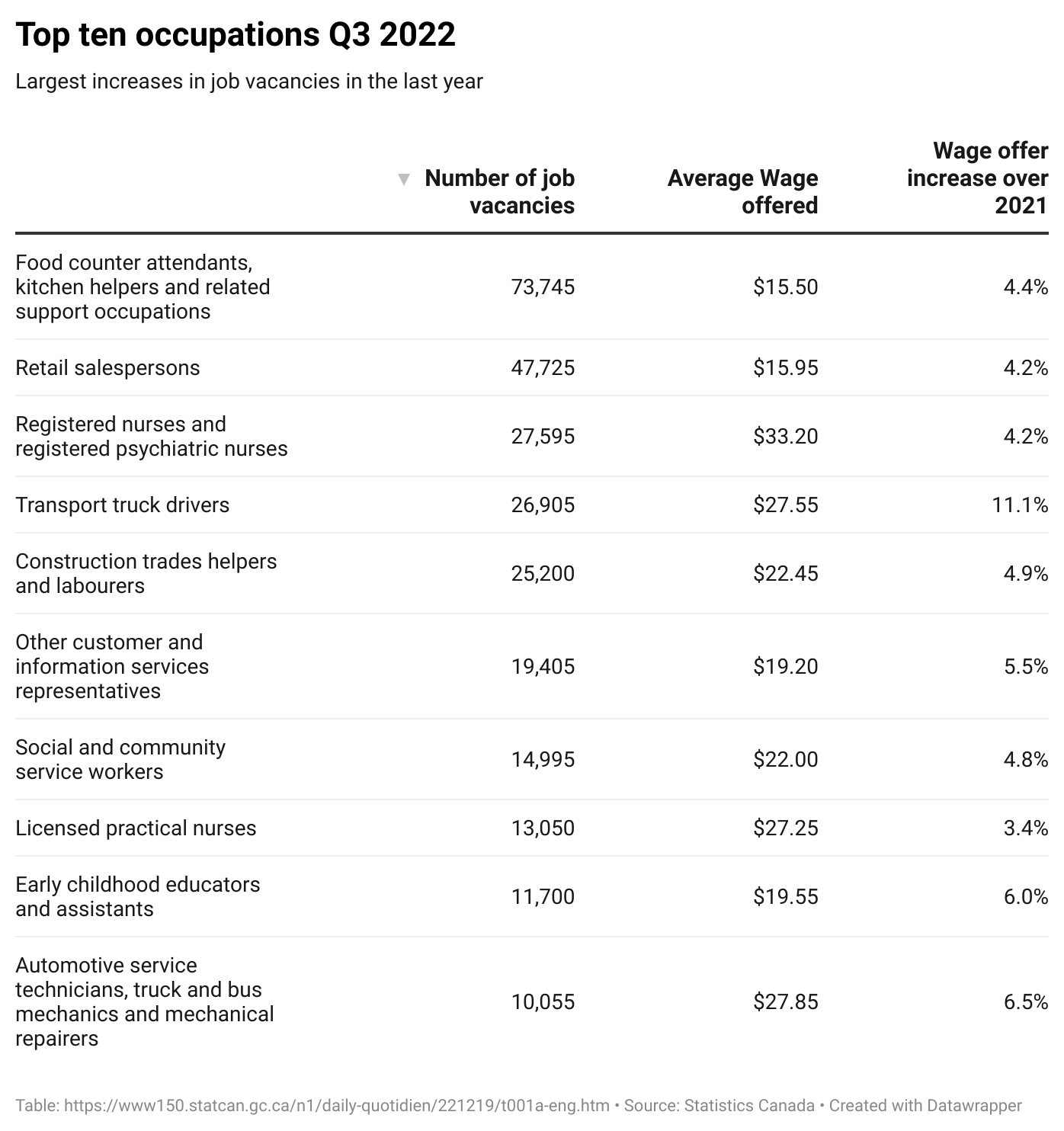

We can also look at the job vacancies by occupation and wage offered - at the end of their analysis today Statistics Canada listed the ten occupation that had job vacancies increase the most over the past year. Only one of the ten occupations had seen their average offered wage increase above the rate of inflation. The two occupations with the largest number of job vacancies pay $15.50/hr and $15.95/hr, and those wages have only increased at 4% during a period when inflation has been at least 7%.

We should be seeing much higher wage growth in these occupations given the size of job vacancies and level of inflation. Economists would expect that workers would be using their significant bargaining power to make up some of the real wage losses we’ve seen in recent years.

Changing labour dynamics

Statistics Canada’s analysis of the latest JVWS survey includes a Beveridge curve - the relationship between unemployment rates and job vacancy rates. They compare a curve modeled on data from 2016-2019 alongside observed values from 2016-2022. While they don’t explicitly say so in their analysis, it shows that observed unemployment rates are higher than we would expect to see given the job vacancy rate - or vice versa. For an unemployment rate of 5%, the modeled curve predicts a job vacancy rate just above 3%, instead of the current 5%. Or, if we hold job vacancies constant instead, a job vacancy rate of nearly 5% predicts an unemployment rate that is a full percentage point lower than it is right now.

Source: Statistics Canada

It definitely looks like something is structurally different about the post-pandemic labour market. When I get a chance I’ll look at the other side of this equation - unemployed and underemployed workers.

Increasing temporary work permits

The federal government’s solution to all of this is very simple - increase the number of temporary foreign worker permits. They are allowing international students and their families to work more, and planning to issue more temporary work permits to family members of current TFWP participants. The Toronto Star has some excellent coverage, here.

Migrant workers rights advocates are rightly concerned that Canada is expanding a second tier of workers without access to the same rights as everyone else. Other workers in Canada should also be concerned that creating a vulnerable second tier of workers makes wages and working conditions worse for everyone. If you want to protect the rights of all workers, check out migrantrights.ca.