Reading the economic tea leaves

Bond prices indicate that financial markets are betting on a recession, but inflationary pressures are easing & labour markets are still strong - could we still get a soft landing?

Financial analysts have been talking a lot about yield curves, and what they predict about the economy. The idea is that investors are making bets about future interest rates whenever they make a decision to buy or sell bonds. Normally, longer term bonds have a higher yield than short term bonds. But when investors are willing to accept lower yields for longer term bonds, it’s a sign that they think the economy is headed for a recession and interest rates will go down.

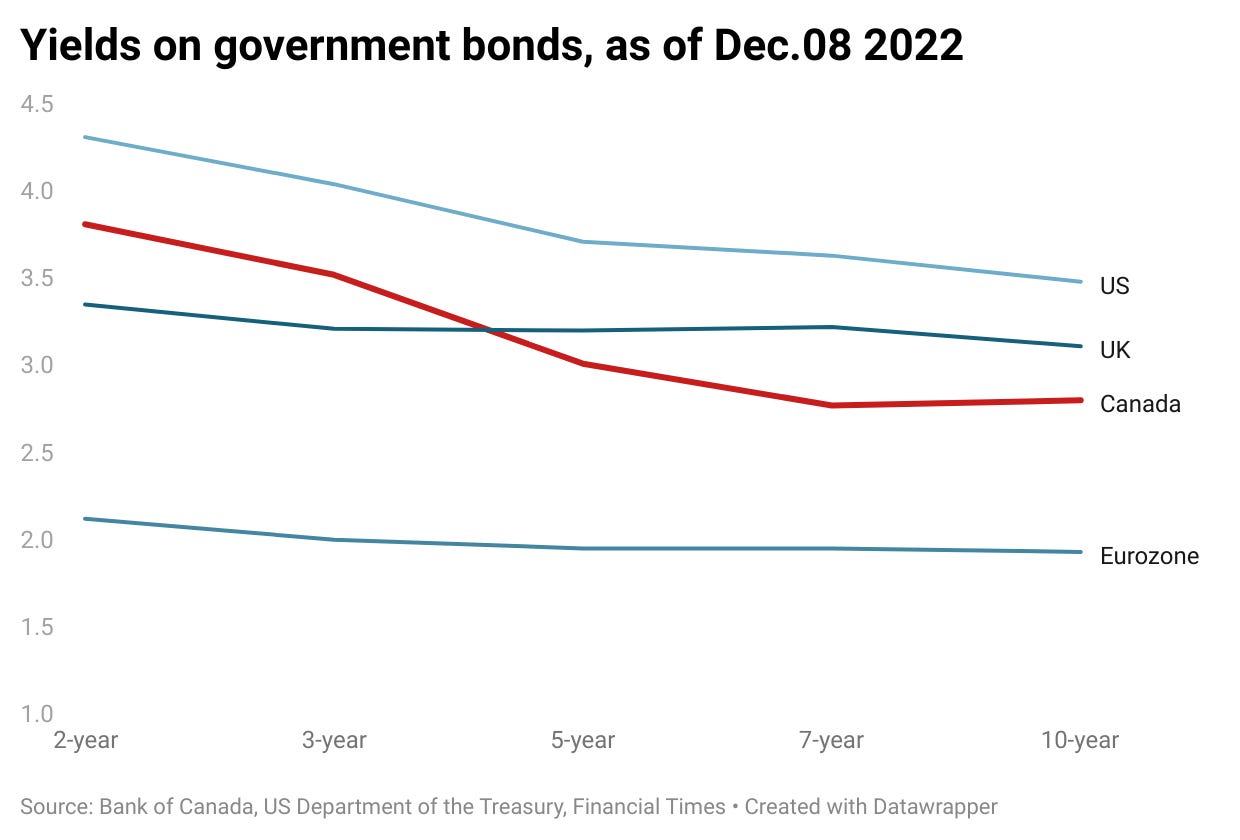

Right now in Canada the 10 year bond yield is a full percentage point lower than the 2 year bond yield.

The yield of a bond is determined by the coupon payment (ex. annual return) divided by the current price. When interest rates go up, the yield of a bond needs to go up in order to be an attractive investment. Since the coupon payment is fixed, the only way to increase the yield is by lowering the price. Alternately, when interest rates go down, bonds are relatively attractive - so their prices rise and their yields fall.

Canada isn’t alone. The yield on 10-year bonds is lower than 2-year bonds for the Eurozone, the UK, and the US right now. But the difference is significantly larger in Canada. The good news is that this means investors are expecting inflation to fall next year. The bad news is they expect that central banks will have to cut interest rates in response to an economic downturn.

Room for optimism

Former Federal Reserve and White House economist Claudia Sahm is more optimistic about the possibility of a soft landing in the US. Inflation is slowing, the labour market is still strong, and the Fed is signaling that it is slowing rate hikes.

Some economists still argue that wage growth and low unemployment are *bad news* for the economy, because they believe it signals continuing inflation. Claudia argues that the old rules don’t apply right now. Wage price spirals aren’t a threat, and the predictive relationship between unemployment and inflation (called the Phillips curve) doesn’t hold. (For a good explainer about the Phillips Curve and why it doesn’t work anymore, see Citizen’s Press.)

On top of that, inflation didn’t come primarily from domestic demand, but from supply chains and elevated energy costs from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The cost of freight is coming down, as are manufacturing delivery times, a sign that supply chains are functioning better.

Monthly CPI is coming down, but since we usually measure the price level compared to the previous year, it can take a while for improvements to show up in that data. Measuring inflation changes over 3 months instead of 12 months can give us a better picture of recent changes in inflation. When we do that, we can see the big increases from the spring and summer are behind us, and recent price changes are lower - although October is going in the wrong direction again.

Will Central Banks allow a soft landing?

Even if a soft landing is possible, will central banks allow it? The optimistic analysis relies on understanding that nominal wage growth and low unemployment doesn’t need to be stamped out. Central banks live and die on their ‘credibility’, the belief that they will force a recession if necessary to get inflation back to 2%. All of the other data will have to be pointing in the right direction before they’ll take that risk.

And that’s what bond markets are predicting. That central banks will go too far, skipping right over a soft landing and into something much messier.