(Un)Employment Insurance and the coming recession

Time to dust off and polish up our automatic stabilizers

In 1995 a federal study found that Unemployment Insurance was ‘the single most powerful automatic stabilizer’ that we have in our fiscal policy toolbox, reducing both GDP and job losses by up to 14% during recessions. Unfortunately, shortly after the recession in the 1990’s the federal government made deep cuts to Unemployment Insurance, and renamed it “Employment Insurance”.

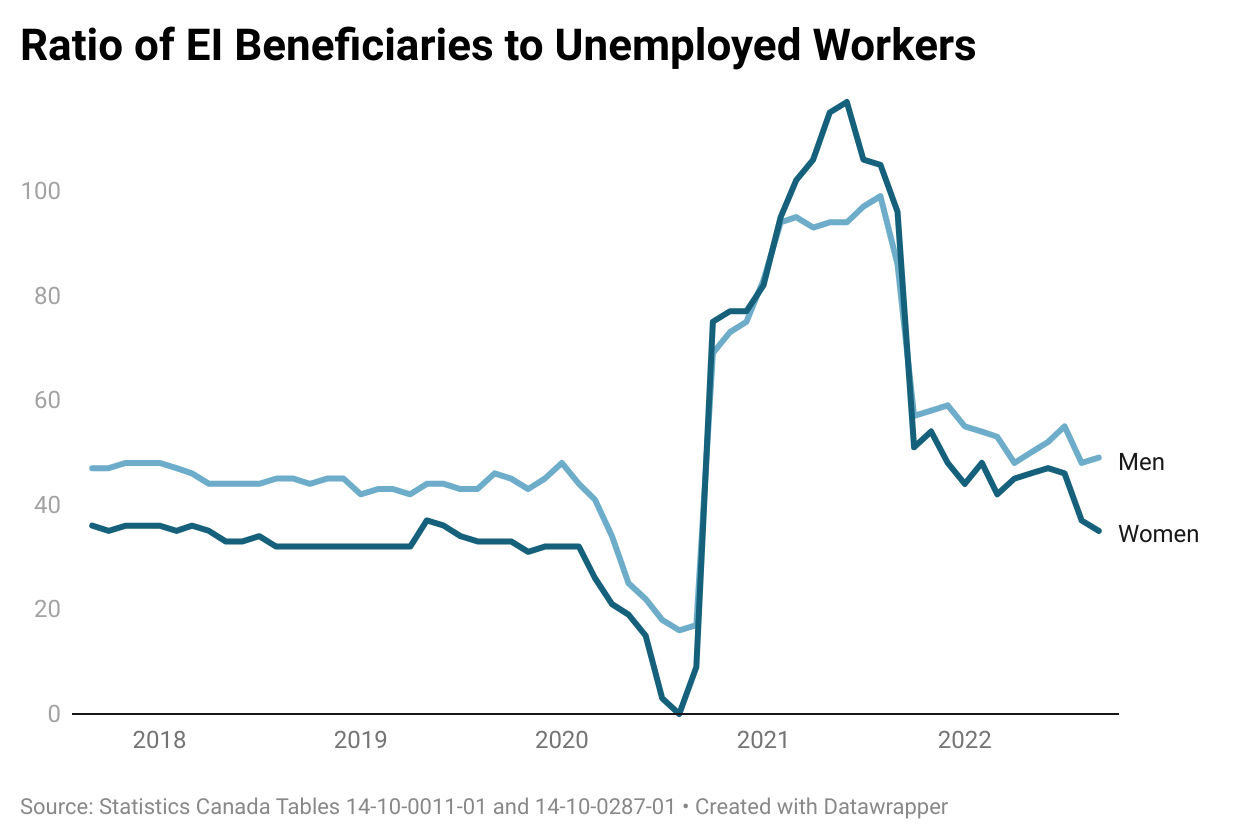

Compounding the cuts, the program failed to adapt to a changing labour market. As full-time “working class” jobs were out-sourced or replaced with more part-time work, more employees being misclassified as self-employed, and more workers with precarious immigration status - fewer workers were covered by EI.

The federal Liberal government has promised to fix EI since it was first elected in 2015. The budget in 2016 undid some of Stephen Harper’s worst changes, but actually reforming the system to better meet the needs of workers has been a long slow slog. Some of the temporary changes brought in during the pandemic opened up access to more precarious workers, but these were removed again in the fall of 2022.

Canada was supposed to get a plan to “modernize” EI in the summer of 2022, which didn’t happen, but there are signs that we might be getting something with the next budget. As the probability of a recession looms larger, these long promised reforms are getting ever more urgent.

Modernize to fit whose purpose?

It’s difficult for a program to stabilize the economy during an economic downturn if the workers most likely to be laid off can’t access it. That’s why the priority of labour unions and unemployed worker’s rights advocates has been to make changes that mean more workers are covered by EI.

One of the ways that EI stabilizes both worker’s incomes and GDP is by giving workers time to find a better job, instead of having to take the first one available. This is good for the worker (obviously), and for overall economic output because that worker is now more productive. Low wage employers don’t like this, because it denies them desperate workers willing to accept low wages and bad working conditions.

A well-functioning social insurance scheme must cover as many workers as it can, and provide them with income for long enough to find a decent job (or retrain for one). There are few changes that will help with that, but employers lobby groups don’t like them, so we’ll have to fight for them.

1. Universal Entrance Requirement of 360 hours

In order to qualify for EI benefits, workers must have paid into the program for a minimum number of hours of work. For regular unemployment benefits, the number varies depending on the 3- month rolling average of the unemployment rate in whichever of the 62 EI economic regions that you live in. This is complicated, messy, and often unfair. A particularly egregious example is Prince Edward Island, where residents of Charlottetown need 700 hours to qualify, and workers living elsewhere on the island only need 560.

Budget 2021 introduced some temporary measures for EI that expired this fall, and one of them was a universal entrance requirement of 420 hours. 420 hours was chosen because it is the current requirement in the highest unemployment regions. Unemployed worker advocates have asked for a lower pan-Canadian entrance requirement of 360 hours. This demand is based on the 12-week standard that applied before the reforms of the 1990’s - 30 hours per week is considered ‘full-time’, so 30 hours * 12 weeks = 360 hours.

2. Simplify EI Regions

The economic region that you live in doesn’t just determine how many hours you need to qualify, it also determines the length of time that you are eligible for benefits. Using the Prince Edward Island example again, the minimum duration for residents of Charlottetown is 14 weeks of benefits, and outside the city it’s 20 weeks.

The assumption is that it will take you less time to find a good job when and where the unemployment rate is lower. But that’s not necessarily true, the regions don’t do a great job of representing a worker’s actual ‘zone of opportunity’, and the unemployment rate indicator is backward looking and slow to respond to big changes in the labour market.

There are a number of fixes that would be helpful here. First, have fewer regions. PEI should only have one EI economic zone, for example. Second, make the difference in benefits between regions smaller. Third, implement some kind of trigger to expand benefits when unemployment increases quickly.

3. Extend EI access to all migrant workers

Migrant workers pay into EI, but often aren’t able to receive it. Even though workers employed through temporary work permits are supposed to be eligible for EI if they meet all of the normal eligibility requirements, too often these workers fall through the cracks. The Migrant Worker’s Alliance of Canada has a great submission outlining why this happens and how we can fix it. Some fixes are within the immigration system, and part of it is within EI itself.

One of the primary barriers for workers on closed permits (when workers are only permitted to work for one employer), is that their immigration status prevents them from being ‘available’ for work. But workers in this category are also denied special benefits, because of a Stephen Harper rule change that required workers to have a valid SIN to receive special benefits if they are living outside of Canada. Since migrant worker SINs expire when they return home, whether for sickness or caregiving leaves, they can no longer access special benefits.

Another issue migrant workers face is difficulty in getting a “Record of Employment” (ROE) from their employer. This is an issue that affects many workers, and gets raised whenever worker advocates meet with Service Canada. Improving access to ROEs in a timely manner would help all workers.

4. Ensure misclassified self-employed workers have access to EI

Self-employed workers can choose to pay into EI, but many don’t, either because it makes financial sense for them to self-insure, or because they can’t afford EI premiums, or because they don’t know it’s an option. Or, because they don’t qualify for regular benefits, only special leaves, it doesn’t seem like a great deal.

Lots of workers who fall into the “can’t afford it” category aren’t really self-employed, they’re just being mis-classified by their employers. When we break out self employment into those that employ others, and those who are on their own, there is a big jump in the more precarious form of self-employment over the latter half of the 1990’s that never really recovered. While some of these workers really are independent contractors, many are being pushed into this mode of employment by employers looking to cut costs.

5. Improve benefit rates

Employment Insurance is not an anti-poverty program - but it does reduce poverty, and could do a better job of that if we wanted it to. Precarious workers with low wages sometimes can’t afford to use EI as it was intended - to take the time to find a decent job, or to take time to care for themselves or loved ones. Low income replacement rates (55%) of low wages effectively make the program inaccessible for many precarious workers. In the past, EI has had both higher replacement rates, and a minimum benefit rate. Either, or both of these options would improve de facto coverage.

The full list is longer

There are lots of other things, big and small, that we could do to improve Employment Insurance. This list is mostly about expanding access, so that at least more workers are covered in the case of job loss. Labour unions and worker advocates will be campaigning for these improvements, hosting rallies, letter writing campaigns, and petitions over the next few months. I’ll share them here as they come up.

We can do hard things

I love the history of Unemployment Insurance in Canada. It came out of worker struggle - men frustrated with the inadequacy of work-camps set up during the Great Depression went on strike. Starting in BC, the strikers tried to make their way to Ottawa, but most of them were stopped in Regina. Some of the leaders went to Ottawa to plead their case, but talks failed and the leaders returned to Regina. On July 1, 1935, RCMP made the questionable decision to arrest strike leaders at a public gathering, leading to a riot, two deaths, and hundreds of injuries.

The On to Ottawa Trek and Regina Riot fueled public and political pressure to create a national income replacement program for unemployed workers. Doing so required a constitutional amendment - it was clearly provincial jurisdiction - but the legislation finally passed in 1940.

I love this history because I take two lessons away from it. The first lesson is that we can do hard things. Sometimes, before we have accomplished a thing, it seems impossible. And on the other hand, once we have accomplished the thing, it seems like it was inevitable that we would be successful. Neither is true. Unemployment insurance was never impossible OR inevitable, and it was not handed to workers without struggle.

The second lesson is that the struggle is never over. Since the 1940’s the program has been amended, added to, reformed, and rethought many times. It has moved beyond its original role as an income stabilizer during periods of unemployment to supporting workers who leave paid work temporarily for other reasons - like parental, compassionate care, and sick leaves. There have been huge wins and huge losses over the lifetime of the program.

We could use another win right about now.